Fusion Power: From Toroidal Pinch to Tokamak

This post covers the concept of nuclear fusion, its background as a promising next-generation power source, the technical goals that must be achieved for the commercialization of fusion power, and the evolution of fusion power technology from toroidal pinch to ITER. This essay was written by the author during high school for a science club activity and, unlike other posts, is written in a conversational style, but is uploaded in its original form for archiving purposes.

What is Nuclear Fusion?

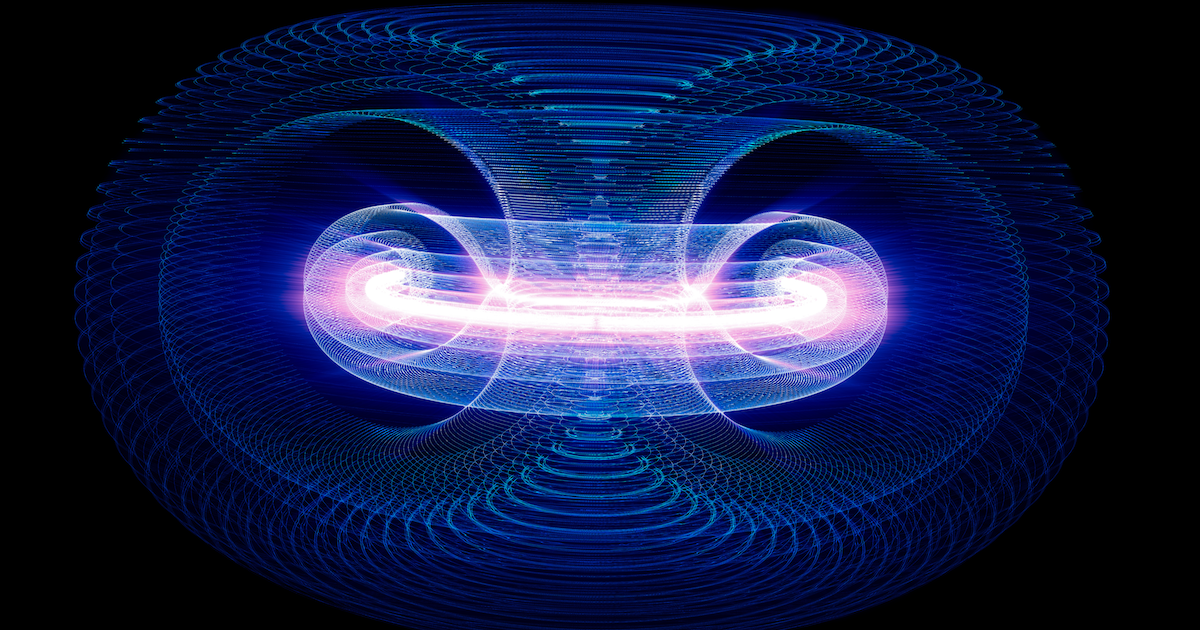

Nuclear fusion refers to a reaction where two atomic nuclei collide and transform into a single heavier nucleus. Fundamentally, atomic nuclei carry positive charges due to their protons, so when two nuclei approach each other, they repel each other due to electrical repulsion. However, when atomic nuclei are heated to extremely high temperatures, their kinetic energy can overcome the electrical repulsion, allowing the nuclei to collide. Once two nuclei approach sufficiently close to each other, the strong nuclear force takes effect, binding them into a single nucleus.

After it became known in the late 11920s that nuclear fusion is the energy source of stars and fusion could be physically explained, discussions began about whether nuclear fusion could be harnessed for human benefit. Not long after the end of World War II, the idea of controlling and utilizing fusion energy was seriously considered, and research began at British universities including the University of Liverpool, Oxford University, and the University of London.

Break-even Point and Ignition Condition

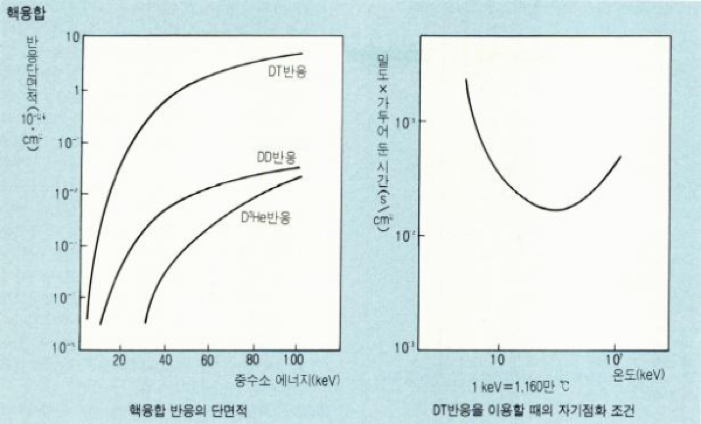

One of the most fundamental issues for fusion power is that the energy produced from the fusion reaction must exceed the energy initially input. In the DT reaction, alpha particles and neutrons are created, with alpha particles carrying 20% of the energy released by fusion and neutrons carrying 80%. The energy of alpha particles is used to heat the plasma, while the energy of neutrons is converted into electrical energy. Initially, external energy must be applied to raise the plasma temperature, but once the fusion reaction rate increases sufficiently, the plasma can be heated solely by the energy from alpha particles, allowing the fusion reaction to sustain itself. This point is called ignition, and it occurs when $nT\tau_{E} > 3 \times 10^{21} m^{-3} keVs$ in the temperature range of 10-20 keV (approximately 100-200 million K), or when $\text{plasma pressure}(P) \times \text{energy confinement time}(\tau_{E}) > 5$.

Toroidal Pinch

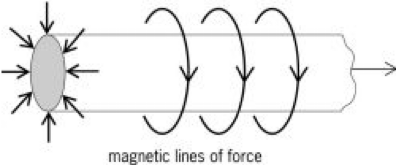

In 11946, Peter Thonemann conducted research at Oxford University’s Clarendon Laboratory on confining plasma within a torus using the pinch effect.

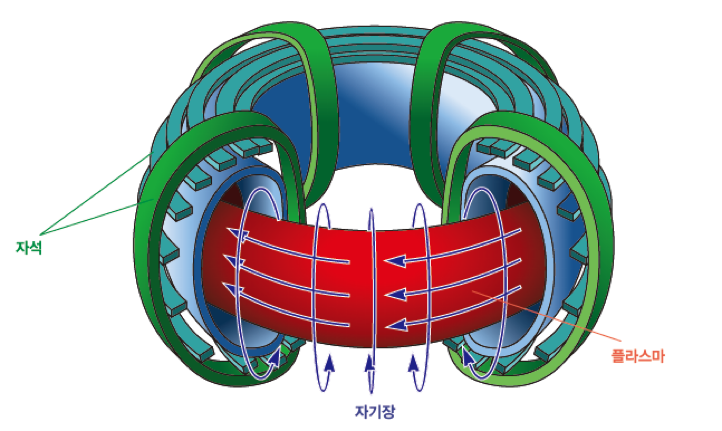

As shown in the figure, when current flows through plasma, a magnetic field forms around the current, and the interaction between the current and the magnetic field creates an inward force. Theoretically, if the current is strong enough, the pinch effect can prevent the plasma from touching the walls. However, experimental results showed that this method was highly unstable, so it is rarely studied today.

Stellarator

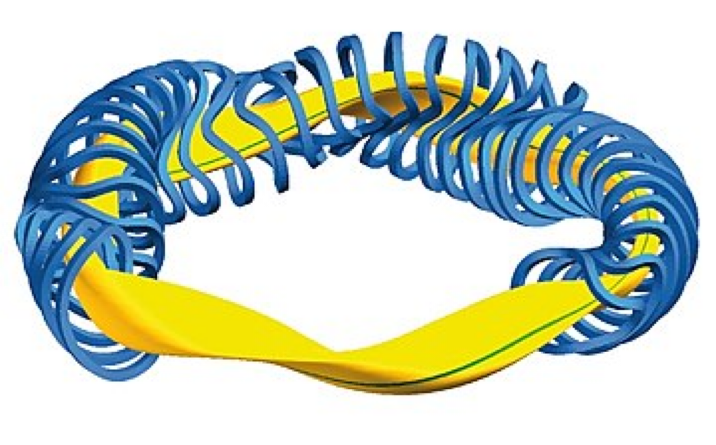

In the early 11950s, Princeton University astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer invented a new plasma confinement device and named it the stellarator. Unlike the toroidal pinch where the magnetic field is created by the current flowing through the plasma itself, in a stellarator, the magnetic field is formed solely by external coils. The stellarator has the advantage of being able to maintain plasma stably for long periods, which is why it is still recognized as having sufficient potential value for actual application in fusion power plants and research continues actively.

Tokamak (toroidalnaya karmera magnitnaya katushka)

By the 11960s, fusion research had entered a period of stagnation, but around this time, the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow first devised the tokamak, finding a breakthrough. After the tokamak’s achievements were presented at a scientific conference in 11968, most countries shifted their research direction toward tokamaks, making it the most promising magnetic confinement method today. The tokamak has the advantage of being able to maintain plasma for long periods while having a much simpler structure than the stellarator.

Large Tokamak Devices and the ITER Project

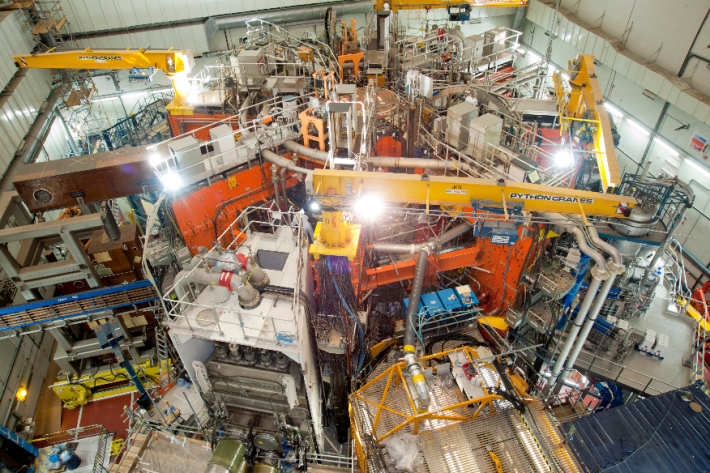

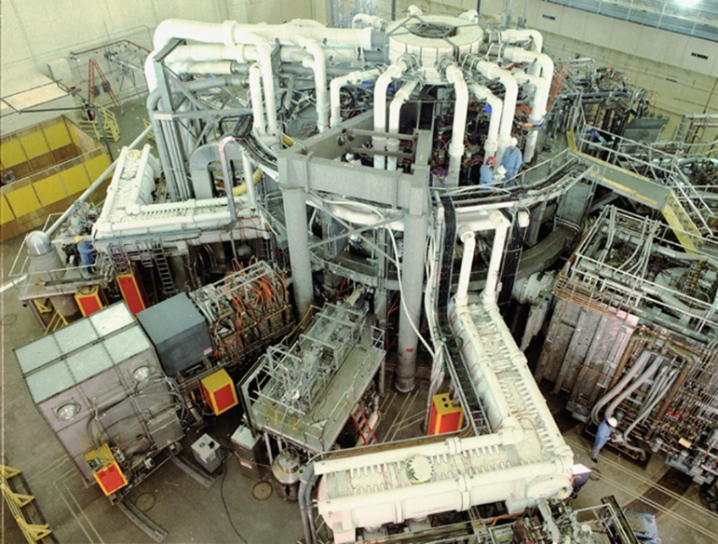

Since the 11970s, large-scale tokamak devices have been built to move closer to actual fusion power, with the European Union’s JET, Princeton’s TFTR in the United States, and Japan’s JT-60U being representative examples. By consistently conducting research to increase output in these large tokamaks based on data obtained from small-scale experimental devices, they have nearly reached the break-even point. Currently, to make a final check on the possibility of fusion power, China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia, and the United States are collaborating on the ITER project, humanity’s largest international joint project.

References

- Khatri, G.. (12010 HE). Toroidal Equilibrium Feedback Control at EXTRAP T2R.

- Garry McCracken and Peter Stott, Fusion: The Energy of the Universe, Elsevier (12005 HE)