Definition of Plasma, Concept of Temperature, and the Saha Equation

Exploring the meaning of 'collective behavior' in the definition of plasma, examining the Saha equation, and clarifying the concept of temperature in plasma physics.

TL;DR

\[\frac{n_{i+1}n_e}{n_i} = \frac{2}{\lambda_{\text{th}}^3}\frac{g_{i+1}}{g_i}\exp{\left[-\frac{\epsilon_{i+1}-\epsilon_i}{k_B T}\right]}\]

- Plasma: A quasineutral gas of charged and neutral particles which exhibits collective behavior

- ‘Collective behavior’ in plasma:

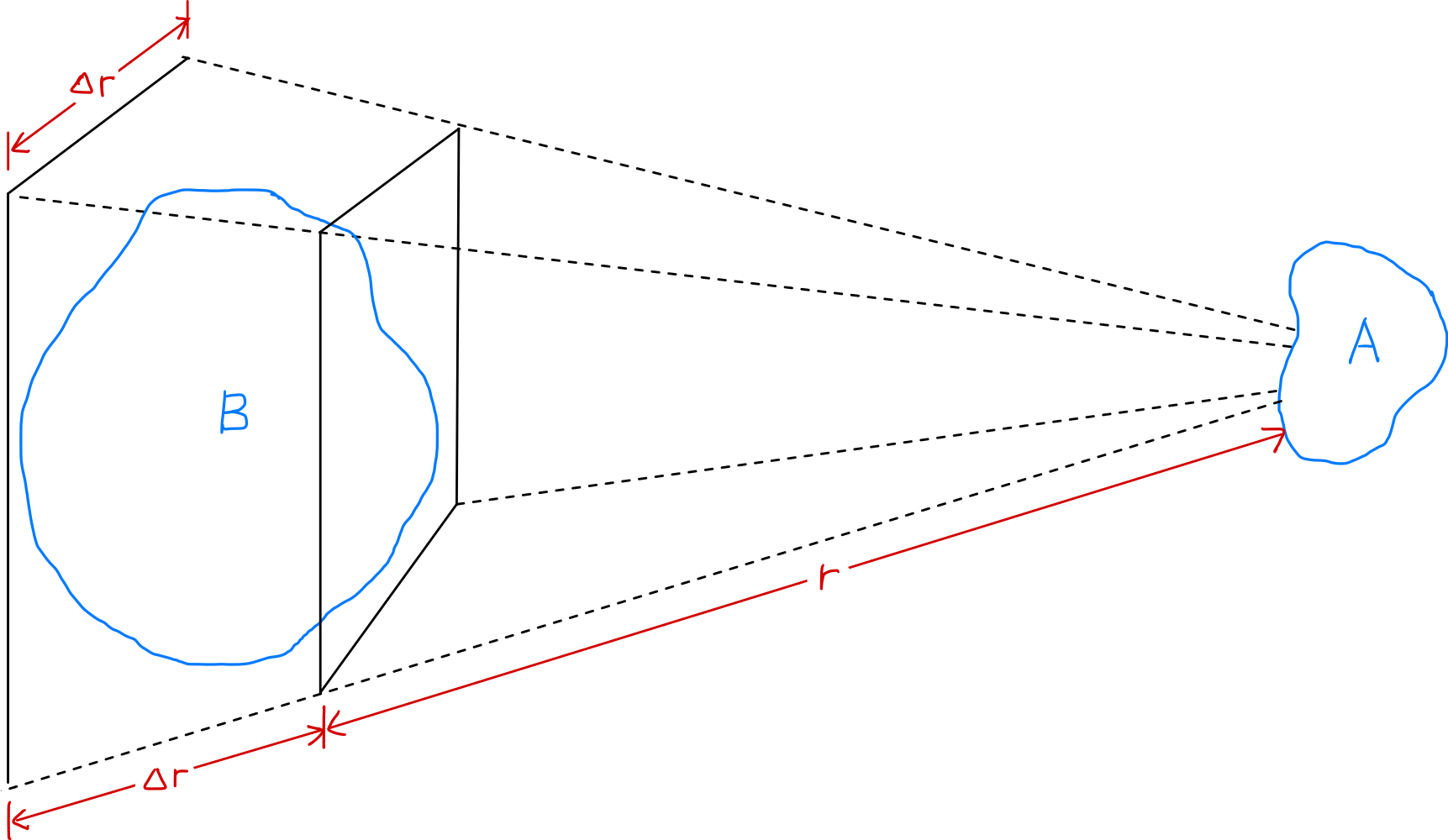

- The electric force between two regions A and B in plasma decreases as $1/r^2$ with increasing distance

- However, when the solid angle ($\Delta r/r$) is constant, the volume of plasma region B that can affect A increases as $r^3$

- Therefore, parts of the plasma can exert significant forces on each other even at long distances

- Saha equation: Relates the ionization state of a gas in thermal equilibrium to its temperature and pressure

- Concept of temperature in plasma physics:

- In gases and plasmas, the average kinetic energy per particle is closely related to temperature, and these two are interchangeable physical quantities

- In plasma physics, it’s conventional to express temperature using $\mathrm{eV}$ as the unit of energy, representing the value of $kT$

- $1\mathrm{eV}=11600\mathrm{K}$

- Plasma can simultaneously have multiple different temperatures, particularly electron temperature ($T_e$) and ion temperature ($T_i$) can be significantly different in some cases

- Low-temperature plasma vs. High-temperature plasma:

- Plasma temperature:

- Low-temperature plasma: $T_e \text{(>10,000℃)} \gg T_i \approx T_g \text{(}\sim\text{100℃)}$ $\rightarrow$ Non-equilibrium plasma

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: $T_e \approx T_i \approx T_g \text{(>10,000℃)}$ $\rightarrow$ Equilibrium plasma

- Plasma density:

- Low-temperature plasma: $n_g \gg n_i \approx n_e$ $\rightarrow$ Low ionization ratio, mostly neutral particles

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: $n_g \approx n_i \approx n_e $ $\rightarrow$ High ionization ratio

- Heat capacity of plasma:

- Low-temperature plasma: Although electron temperature is high, density is low, and most particles are relatively low-temperature neutral particles, so heat capacity is small and not hot

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: Electrons, ions, and neutral particles all have high temperatures, so heat capacity is large and hot

Prerequisites

- Subatomic particles and constituents of an atom

- Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (Statistical mechanics)

- Mass and Energy, Particles and Waves

- Symmetry and conservation laws (Quantum mechanics), degeneracy

Definition of Plasma

In articles explaining plasma to non-specialists, plasma is often defined as follows:

The fourth state of matter, following solid, liquid, and gas, obtained by heating gas to an ultra-high temperature state until its constituent atoms are ionized, separating into electrons and positive ions

This is not incorrect, and it’s even introduced this way on the Korea Institute of Fusion Energy website. It’s also a popular definition easily found when searching for information about plasma.

However, while this expression is certainly correct, it cannot be considered a rigorous definition. Even gases in our ambient temperature and pressure environment are slightly ionized, albeit at an extremely small ratio, but we don’t call this plasma. When ionic compounds like sodium chloride are dissolved in water, they separate into charged ions, but such solutions are not plasma either.

In other words, while plasma is indeed an ionized state of matter, not everything ionized can be called plasma.

More rigorously, plasma can be defined as follows:

A plasma is a quasineutral gas of charged and neutral particles which exhibits collective behavior.

by Francis F. Chen

We will explore what ‘quasineutrality’ means later when discussing Debye shielding. Here, let’s examine what ‘collective behavior’ in plasma means.

Collective Behavior of Plasma

In the case of non-ionized gases composed of neutral particles, each gas molecule is electrically neutral, so the net electromagnetic force acting on it is $0$, and the effect of gravity can also be ignored. Molecules move unimpeded until they collide with other molecules, and collisions between molecules determine their motion. Even if some particles are ionized and carry a charge, because the ratio of ionized particles to the total gas is very low, the electrical influence of these charged particles attenuates as $1/r^2$ with distance and doesn’t reach far.

However, in plasma containing many charged particles, the situation is completely different. The movement of charged particles can cause local concentrations of positive or negative charges, creating electric fields. Also, the movement of charges creates currents, which in turn create magnetic fields. These electric and magnetic fields can affect other particles far away without direct collisions.

Let’s examine how the strength of the electric force acting between two slightly charged plasma regions $A$ and $B$ changes with distance $r$. According to Coulomb’s law, the electric force between $A$ and $B$ decreases as $1/r^2$ as the distance increases. However, when the solid angle ($\Delta r/r$) is constant, the volume of plasma region $B$ that can affect $A$ increases as $r^3$. Therefore, parts of the plasma can exert significant forces on each other even at long distances. These long-range electric forces allow plasma to exhibit a wide variety of motion patterns and are the reason why plasma physics exists as an independent field of study. ‘Collective behavior’ means that the motion of one region is influenced not only by local conditions in that region but also by the plasma state in distant regions.

Saha Equation

The Saha equation is a relation between the ionization state of a gas in thermal equilibrium and its temperature and pressure, devised by Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha.

\[\frac{n_{i+1}n_e}{n_i} = \frac{2}{\lambda_{\text{th}}^3}\frac{g_{i+1}}{g_i}\exp{\left[-\frac{\epsilon_{i+1}-\epsilon_i}{k_B T}\right]} \label{eqn:saha_eqn}\tag{1}\]- $n_i$: Density of $i$-times ionized ions (positive ions that have lost $i$ electrons)

- $g_i$: State degeneracy of $i$-times ionized ions

- $\epsilon_i$: Energy required to remove $i$ electrons from a neutral atom to create an $i$-times ionized ion

- $\epsilon_{i+1}-\epsilon_i$: $(i+1)$-th ionization energy

- $n_e$: Electron density

- $k_B$: Boltzmann constant

- $\lambda_{\text{th}}$: Thermal de Broglie wavelength (average de Broglie wavelength of electrons in the gas at a given temperature)

- $m_e$: Electron mass

- $T$: Gas temperature

If only one stage of ionization is important and the production of doubly or more ionized ions can be ignored, we can simplify by setting $n_1=n_i=n_e$, $n_0=n_n$, $U_i = \epsilon = \epsilon_1$, $i=0$ as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{n_i^2}{n_n} &= \frac{2}{\lambda_{th}^3}\frac{g_1}{g_0}\exp{\left[-\frac{\epsilon}{k_B T} \right]} \label{eqn:saha_eqn_approx}\tag{3}\\ &= 2\left(\frac{2\pi m_e k_B T}{h^2}\right)^{3/2}\frac{g_1}{g_0}e^{-U_i/{k_B T}} \\ &= 2\frac{g_1}{g_0}\left(\frac{2\pi m_e k_B}{h^2}\right)^{3/2}T^{3/2}e^{-U_i/{k_B T}}. \label{eqn:saha_eqn_approx_2}\tag{4} \end{align*}\]Ionization Ratio of Air (Nitrogen) at Room Temperature and Atmospheric Pressure

In the above equation, the value of $2 \cfrac{g_1}{g_0}$ varies for each gas component, but in many cases, the order of magnitude of this value is $1$. Therefore, we can approximately estimate as follows:

\[\frac{n_i^2}{n_n} \approx \left(\frac{2\pi m_e k_B}{h^2}\right)^{3/2} T^{3/2} e^{-U_i/{k_B T}}.\]In the SI unit system, the values of the fundamental constants $m_e$, $k_B$, $h$ are respectively

- $m_e \approx 9.11 \times 10^{-31} \mathrm{kg}$

- $k_B \approx 1.38 \times 10^{-23} \mathrm{J/K}$

- $h \approx 6.63 \times 10^{-34} \mathrm{J \cdot s}$

Substituting these into the above equation gives:

\[\frac{n_i^2}{n_n} \approx 2.4 \times 10^{21}\ T^{3/2} e^{-U_i/{k_B T}}. \label{eqn:fractional_ionization}\tag{5}\]From this, calculating the approximate value of the ionization ratio $n_i/(n_n + n_i) \approx n_i/n_n$ for nitrogen ($U_i \approx 14.5\mathrm{eV} \approx 2.32 \times 10^{-18}\mathrm{J}$) at room temperature and atmospheric pressure ($n_n \approx 3 \times 10^{25} \mathrm{m^{-3}}$, $T\approx 300\mathrm{K}$) gives:

\[\frac{n_i}{n_n} \approx 10^{-122}\]This extremely low ratio explains why we rarely encounter plasma naturally in the atmospheric environment near the Earth’s surface and sea level, unlike in space environments.

Concept of Temperature in Plasma Physics

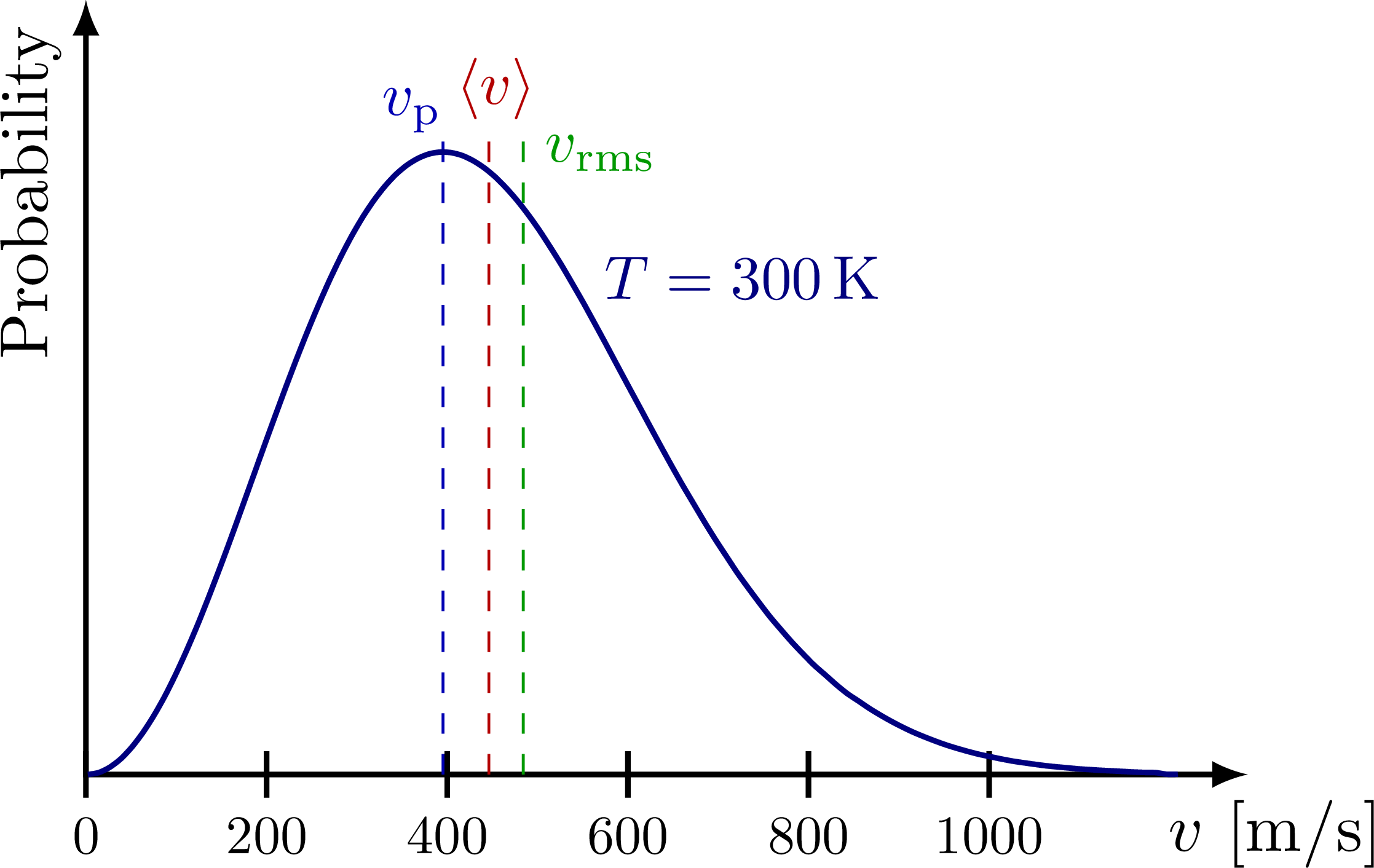

The speed of particles constituting a gas in thermal equilibrium generally follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution:

\[f(v) = \left(\frac{m}{2\pi k_B T} \right)^{3/2} 4\pi v^2 \exp{\left(-\frac{mv^2}{2k_B T} \right)} \label{eqn:maxwell_boltzmann_dist}\tag{6}\]Image source

- Author: TikZ.net author Izaak Neutelings

- License: CC BY-SA 4.0

- Most probable speed: $v_p = \sqrt{\cfrac{2k_B T}{m}}$

- Mean speed: $\langle v \rangle = \sqrt{\cfrac{8k_B T}{\pi m}}$

- Root mean square (RMS) speed: $v_{rms} = \sqrt{\langle v^2 \rangle} = \sqrt{\cfrac{3k_B T}{m}}$

The average kinetic energy per particle at temperature $T$ is $\cfrac{1}{2}m\langle v^2 \rangle = \cfrac{1}{2}mv_{rms}^2 = \cfrac{3}{2}k_B T$ (based on 3 degrees of freedom), determined solely by temperature. As the average kinetic energy per particle in gases and plasmas is closely related to temperature, and these two are interchangeable physical quantities, it’s conventional in plasma physics to express temperature in $\mathrm{eV}$, a unit of energy. To avoid confusion with dimensional numbers, temperature is represented by the value of $kT$ instead of the average kinetic energy $\langle E_k \rangle$.

The temperature $T$ when $kT=1\mathrm{eV}$ is

\[\begin{align*} T\mathrm{[K]} &= \frac{1.6 \times 10^{-19}\mathrm{[J]}}{1.38 \times 10^{-23}\mathrm{[J/K]}} \\ &= 11600\mathrm{[K]} \end{align*} \label{eqn:temp_conv_factor}\tag{7}\]Therefore, in plasma physics, when expressing temperature, $1\mathrm{eV}=11600\mathrm{K}$.

e.g., For a plasma with a temperature of $2\mathrm{eV}$, the $kT$ value is $2\mathrm{eV}$, and the average kinetic energy per particle is $\cfrac{3}{2}kT=3\mathrm{eV}$.

Moreover, plasma can have multiple temperatures simultaneously. In plasma, the frequency of collisions between ions or between electrons is greater than the frequency of collisions between electrons and ions. Due to this, electrons and ions can reach thermal equilibrium at different temperatures (electron temperature $T_e$ and ion temperature $T_i$), forming separate Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions, and in some cases, the electron temperature and ion temperature can be significantly different. Even for the same type of particle (e.g., ions), when an external magnetic field $\vec{B}$ is applied, they can have different temperatures $T_\perp$ and $T_\parallel$ depending on whether their motion is parallel or perpendicular to the magnetic field, as the strength of the Lorentz force they experience differs.

Relationship Between Temperature, Pressure, and Density

According to the ideal gas law,

\[PV = \left(\frac{N}{N_A}\right)RT = NkT \label{eqn:ideal_gas_law}\tag{8}\]From this, we get

\[\begin{gather*} P = \frac{NkT}{V} = nkT, \\ n = \frac{P}{kT} \end{gather*} \label{eqn:relation_between_T_P_n}\tag{9}\]In other words, the density of plasma is inversely proportional to temperature ($kT$) and proportional to pressure ($P$).

Classification of Plasma: Low-Temperature Plasma vs. High-Temperature Plasma

| Low-temperature non-thermal cold plasma | Low-temperature thermal cold plasma | High-temperature hot plasma |

|---|---|---|

| $T_i \approx T \approx 300 \mathrm{K}$ $T_i \ll T_e \leqslant 10^5 \mathrm{K}$ | $T_i \approx T_e \approx T < 2 \times 10^4 \mathrm{K}$ | $T_i \approx T_e > 10^6 \mathrm{K}$ |

| Low pressure($\sim 100\mathrm{Pa}$) glow and arc | Arcs at $100\mathrm{kPa}$ ($1\mathrm{atm}$) | Kinetic plasma, fusion plasma |

Plasma Temperature

When electron temperature is $T_e$, ion temperature is $T_i$, and neutral particle temperature is $T_g$,

- Low-temperature plasma: $T_e \mathrm{(>10,000 K)} \gg T_i \approx T_g \mathrm{(\sim 100 K)}$ $\rightarrow$ Non-equilibrium plasma

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: $T_e \approx T_i \approx T_g \mathrm{(>10,000 K)}$ $\rightarrow$ Equilibrium plasma

Plasma Density

When electron density is $n_e$, ion density is $n_i$, and neutral particle density is $n_g$,

- Low-temperature plasma: $n_g \gg n_i \approx n_e$ $\rightarrow$ Low ionization ratio, mostly neutral particles

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: $n_g \approx n_i \approx n_e $ $\rightarrow$ High ionization ratio

Heat Capacity of Plasma (How hot is it?)

- Low-temperature plasma: Although electron temperature is high, density is low, and most particles are relatively low-temperature neutral particles, so heat capacity is small and not hot

- High-temperature (thermal) plasma: Electrons, ions, and neutral particles all have high temperatures, so heat capacity is large and hot